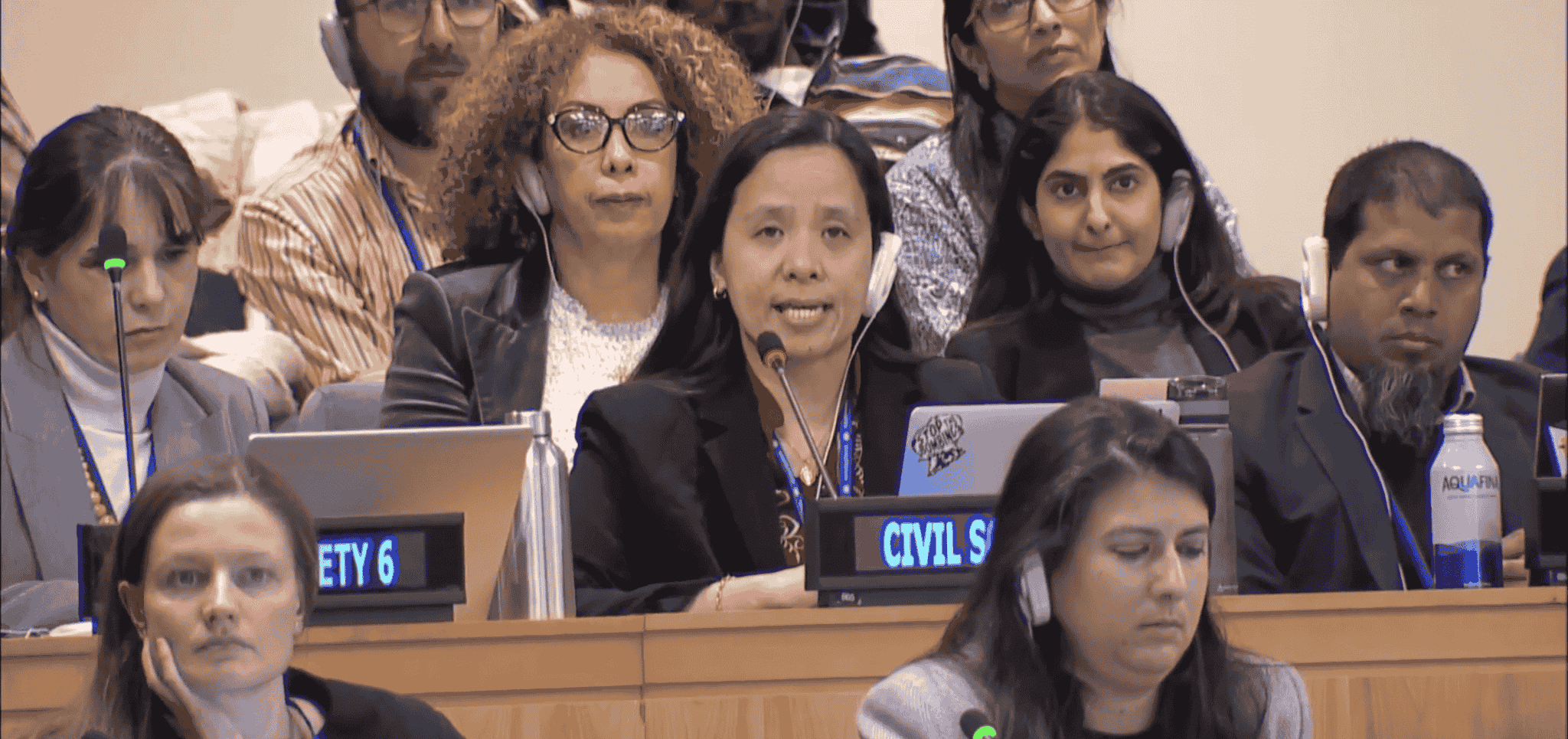

On March 14, 2023, at the 2023 UN Development Cooperation Forum (DCF), Jennifer del Rosario-Malonzo of IBON International served as a lead discussant at the session on development co-operation and climate resilience. Below is her input, as delivered in the session.

I speak not just on behalf of my organisation, IBON International, but also of the Civil Society Financing for Development (FfD) Mechanism and the CSO Partnership for Development Effectiveness. In our era of multiple crises, we appreciate this year’s DCF focus on development co-operation’s role in addressing multidimensional vulnerabilities, such as due to climate change.

We agree with the need for effective development co-operation for climate resilience. We believe that we also have to address its opposite: ineffective development cooperation that contributes to climate risks and harms.

As it is, climate change impacts are already breaching the adaptation limits of nations and communities, amid more frequent and severe disasters. The global South does not have strong safety nets and resources to deal with such impacts. Marginalised sectors, from farmers, fisherfolk, workers, women, LGBTQIA+, to people of color, youth, Indigenous Peoples, and people with disabilities, are already socially and economically at a disadvantage, limiting their capacity to adapt.

It is thus concerning when development co-operation is leading to projects that dispossess communities, such as in the case of continued donor financing of the Jalaur Mega Dam in the Philippines despite the documented killings and rights violations in 2021 against indigenous communities that have opposed the project.

Communities especially in the global South cannot withstand climate shocks if development interventions take away their resources to protect themselves. Climate risks of communities worsen from unsustainable projects in development co-operation, which sustain extractivist economic models. Not only such cases run counter to democratic ownership, meaningful results, and the right to self-determination. These also increase communities’ risks to extreme weather events, make them economically vulnerable, and worsen their marginalisation.

Other issues mark quantity and quality of financing. The 100-billion-dollar climate finance target has not been delivered. A very small percentage is new and additional to Official Development Assistance (ODA), and most are in loans. As it is, more than 80% of island states are already in debt distress.

Developed countries are also double counting by rebadging their existing financial commitments. Rebadging official aid as loss and damage finance, for example, will further fragment and shrink the already paltry resources going towards economic development and welfare of developing countries.

Finally, effective development co-operation means peoples and Southern countries are allowed to identify their own priorities in addressing climate change impacts, and thus where they need co-operation in forms of financing, capacity development, policy changes, and partnerships.

It also means striking at the structural roots of climate and economic vulnerabilities: of shaping paths that are democratically-led and owned, attuned to people’s needs, especially of women and other marginalised sectors, and are accountable to rights-holders. It means supporting shifts to development models that uphold peoples’ rights over their resources.

Finance-wise, the establishment of a funding mechanism specific for loss and damage at COP27 was an important initial step. We need effectiveness to inform climate finance mechanisms, as well as uphold principles of equity and Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). We also need additionality—not creative rebadging of aid.