Climate change has been causing severe damage to millions of African people, particularly the poor. The climate crisis exacerbates food insecurity and aggravating conflicts over shrinking resources, such as water and grazing lands. African countries require financing to enhance their adaptation to the impacts of climate change. At a time when millions of people are being displaced due to climate disasters, the challenge for governments and leaders is to commit and act according to imperatives of climate justice.

The 28th Conference of Parties (COP28) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held in the United Arab Emirates in late 2023 was a space where civil society organisations (CSOs) and social movements urged global leaders to prioritise realistic and people-centred measures to combat the escalating climate emergency.

During the last climate talks, African civil society organisations were yet again disappointed as world leaders failed to fully commit to phase out fossil fuels, the main drivers of climate change.

With only around half a year before COP29, IBON Africa recaptures some of the outcomes of the last summit to reflect on possibilities and limitations of the upcoming UN climate conversations.

Outcomes of the Global Stocktake: A licence for business-as-usual

The Global Stocktake is a five-year status check on climate action, which is measured against the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement. The Global Stocktake is intended to evaluate progress on climate action at global level to identify gaps and opportunities to bridge those gaps, as well as inform countries in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

The stocktake is part of the UAE Consensus. While it was a first in the international climate negotiations, the outcomes of the first stocktake have huge gaps in terms of its aspirations and also in ensuring it delivers climate justice. There were no concrete provisions on how the transition will happen and who should lead it. This leaves room for continued use of fossil fuels, and a likelihood of deepening and prolonging risks associated with climate change to most of the global South. Communities need a commitment especially from the global North to phase out fossil fuels completely.

The outcomes of the first Global Stocktake also gives the fossil fuel industry a licence to continue their “business as usual” practices by welcoming the industry’s call to accelerate climate mitigation technologies that are unproven and risky, such as carbon removal methods, carbon capture and storage, and geoengineering.

Meanwhile, financial commitments at COP28 for the transition were inadequate. Eight donor governments announced new commitments of USD 174 million to the Least Developed Countries Fund and the Special Climate Change Fund.New pledges amounting to USD 188 million were also made for the Adaptation Fund . However, all these fall short of the trillions needed for developing countries’ adaptation.

The World Bank’s capture of the Loss and Damage Fund

The Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) aims to provide remedies to communities that face the worsening impacts of climate change in order for them to rebuild their lives and livelihood. Essentially, the loss and damage fund provides a reparative mechanism for historic emitters to transfer disaster recovery reparations to developing nations.

During COP27 in 2022, there was a concerted push from developing nations to establish the LDF. A transitional committee was formed to agree on the details of this fund, which include the Fund’s manager, total budget, and country contributors as well as donors.

On November 30, 2023, the recommendations from the Transitional Committee of the LDF was officially adopted, marking the first time a substantial outcome was achieved during an opening session of a COP. However, many other decisions at COP28 made the agreement resemble a symbolic concession rather than real action.

The terms adopted for the operationalisation of the fund remains highly contentious: there is no firm obligation for the global North to pay for reparations as it is on a voluntary basis. To no surprise, developed countries only pledged a few hundred million dollars, while billions of dollars were needed to make the LDF effective. In total, the fund garnered USD $770.6 million by the end of COP28, which is quite below the damages experienced in the Africa region, which is projected to rise to USD 400 billion annually and therefore the total amount pooled is not even enough for Africa’s loss and damage costs.

The UAE was the first to pay, launching a USD 100 million contribution, followed by Germany which also contributed the same amount. The UK, EU, and Japan followed with USD 75 million, USD 245 million and USD 10 million respectively. The United States committed only USD 17.5 million which was highly criticised since it is the largest historic and current emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG).

Countries agreed that the LDF would be housed under the World Bank for at least four years, as an independent entity under the UNFCCC financial mechanism. Previously, developing countries as well as CSOs were objecting to the hosting of the World Bank due to its record of financing fossil fuels projects and debt-driven financing.

Considering that the goal is to have the LDF up and running by 2024, the committee resolved to recommend the World Bank to serve as the LDF host. This fueled divisions between developed and developing countries.To get all countries on board, it was agreed that the World Bank will serve as an interim host for four years with developing countries signing up on a set of conditions. These conditions state that governments and non-traditional implementing entities particularly those beyond multilateral and regional development banks and United Nations agencies can access the fund directly.

Civil society organisations from the global South particularly from Africa expressed that it is crucial for affected communities to participate in decision-making processes and to be able to access the fund.

Adaptation: The erosion of the “common but differentiated responsibilities” principle

Adaptation has been a priority for most of the global South , particularly African countries which proposed the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). The GGA has received little attention within the United Nations negotiations until COP26 in Glasgow, United Kingdom where the African Group pushed successfully for a two-year work programme. In work programme meetings, which wrapped up in COP28, countries were tasked to agree on a framework that nations could use in guiding their adaptation progress. The framework for the GGA was the main output. Parties agreed on the themes to be covered by GGA, which include water, health, ecosystems, infrastructure, cultural heritage and poverty eradication.

However, the agreed GGA text at COP28 lacks reference to the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities, despite the insistence of African countries.It only recalls the provisions of the UNFCCC and the principles of the Paris Agreement.

While progress on global climate financing has increased from USD 653 billion in 2019-2020 to USD 1.3 trillion in 2021-2022, the portion of adaptation finance has decreased significantly from 7% to 5% of the total climate finance in the period. Compared to mitigation, developing countries are struggling to get funding for adaptation programs.

Africa, being the most impacted by the climate crisis, only received 20% of global adaptation finance flows (at USD 13 billion annually) in 2021-2022. Meanwhile, about 80% of adaptation finance in the region comes in the form of loans with conditions. Considering that African countries are grappling with debt, it is crucial to mobilise substantial grants for adaptation. Adaptation finance is key in enhancing resilience of African communities to the impacts of climate change.

Corporate capture through market-based mechanisms

There was no decision adopted regarding market-based mechanisms such as carbon trading during COP28. Countries did not agree on: the activities that are eligible to be included in carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement; the processes of correcting inconsistencies in country reports; and the process of authorising emissions reductions for transfer to other countries. The negotiations are expected to resume during COP29.

Carbon trading is about buying permissions to continue emitting or polluting, instead of ensuring genuine emissions reductions at their source. Therefore, multinational corporations and industries can claim to have a lower impact on climate by buying carbon credits from projects elsewhere. These projects claim to have somehow avoided emissions or taken carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Carbon trading has huge implications, such as displacement of communities from their land. Nature-based offset projects, such as planting new forests, require vast areas of land result in the eviction of communities already living in those lands. There are restrictions in terms of access to land particularly community land and human rights violations in these sectors. The global South continues to grapple with detrimental impacts of climate change such as rising sea levels, recurrent droughts, floods and increased temperatures. This is because big polluters are promoting offsets projects and continuing their harmful activities instead of reducing emissions at source.

Towards COP29: Limitations and possibilities

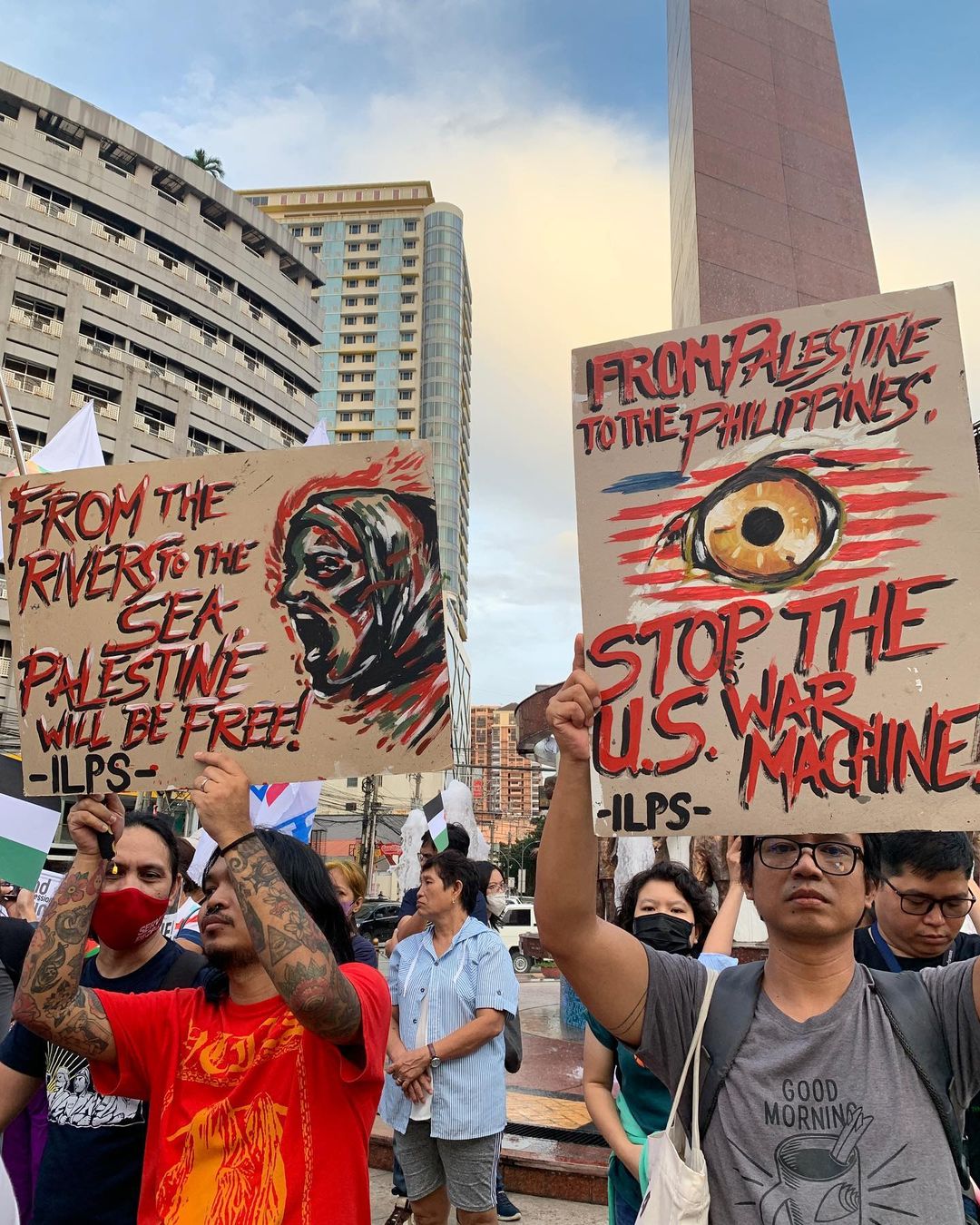

It is crucial for CSOs to continue pushing for people-centred actions and solutions that place peoples’ rights and sovereignty front and centre of negotiations and decisions. There is a need to continue expanding the existing capacities of communities in advancing climate justice, including advocating against greenwashing and the imposition of market-based mechanisms such as carbon trading in order to challenge the corporate capture of the climate agenda.

Meanwhile, COP 29 will be held in Azerbaijan, an authoritarian country that highly represses association, and peaceful assembly, as well as freedom of expression. As With the country’s main source of income comes from is oil and gas export revenues from its oil and gas exports, CSOs raise concerns over the suitability of Azerbaijan to host COP29. The probability of the conference to serving the interests of the host country and those of the fossil fuel industry remains high.

CSOs must continue to pressure governments, particularly the global North countries to turn their so-called pledges into real actions. CSOs across the world through their alliances and movements are key in ensuring accountability within the climate change discourse and in all development processes at national, regional and global level. With regards to COP29, this calls for the following:

- Developed countries must lead in the phase out of all fossil fuels and increase their nationally determined contributions and targets to limit global warming.

- Reject false climate ‘solutions’ such as carbon markets, carbon capture, and nature-based solutions that prolong dependence on fossil fuels. Mechanisms that trade in carbon credits obtained from dubious projects that violate the rights of communities, especially women and Indigenous Peoples, must be immediately stopped.

- Developed countries should ramp up their financial commitments towards developing countries’ transition, adaptation, and loss and damage costs, guided by the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities-respective capacities (CBDR-RC).

- Countries and communities in the frontlines and who have been hugely affected by climate change should lead in the decision-making process and governance of the Loss and Damage Fund.

- The UNFCCC should develop a robust accountability mechanism ensuring that representatives of the fossil fuel industry and multinational corporations are unable to engage and influence the outcomes of UNFCCC processes, whose main interest is to prevent the shift away from fossil fuel dependence.

- Ensure that COP29 will be people-centred and inclusive; promote meaningful participation by local communities and Indigenous Peoples, climate activists, human rights defenders, and peoples’ organisations marginalised groups and sectors to ensure that peoples’ rights are at the front and centre of negotiations and meetings.

Communities must remain vigilant of the corporate capture of the climate agenda promoted through false solutions such as carbon trading and so-called nature-based solutions peddled by multinational corporations and the global North. Beyond the climate talks, it is imperative for grassroots organisations and communities to organise and mobilise to push for a systemic change that addresses the root causes of climate change in the current monopoly capitalist system.