Photo by: People Over Profit

RCEP heavily favors multinational corporations who are also some of the key figures in the negotiations – at the expense of peoples’ rights and any prospect towards sustainability.

As the world continues to find its bearings amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the 10-member ASEAN bloc – Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam – together with Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea concluded negotiations on the highly controversial Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) at the sidelines of the 37th ASEAN Summit last November 15. The year 2021 is supposed to be the year for the ratification of the RCEP at country level, and the trade deal could become effective by late 2021 or early 2022.

The now publicly released RCEP documents have confirmed the suspicions of civil society worldwide – RCEP heavily favors multinational corporations who are also some of the key figures in the negotiations – at the expense of peoples’ rights and any prospect towards sustainability.

And yet, proponents of this trade would go so far as to say in their joint leaders’ statement that RCEP “is critical for our region’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and will play an important role in building the region’s resilience through inclusive and sustainable post-pandemic economic recovery process[1]” – a highly unlikely prospect given the pernicious consequences of this deal to both the people and the planet.

Like other 21st century Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), RCEP has been fraught with criticisms on many of its neoliberal provisions which will only reinforce the unbridled plunder of the Global South’s natural resources as well as the exploitation of its peoples. RCEP is also notorious for its highly secretive and undemocratic trade committee meetings that most notably excluded civil society and people’s organizations.

Despite the secretive nature of the negotiations, IBON International has actively fought for democratic spaces to engage RCEP’s Trade Negotiating Committee for many years now seeking to expose its neoliberal and anti-people provisions that will make life-saving medicines less accessible to the public, intensify land grabs in the region, push for the privatization of seeds, and ultimately undermine local food production systems especially among developing countries.

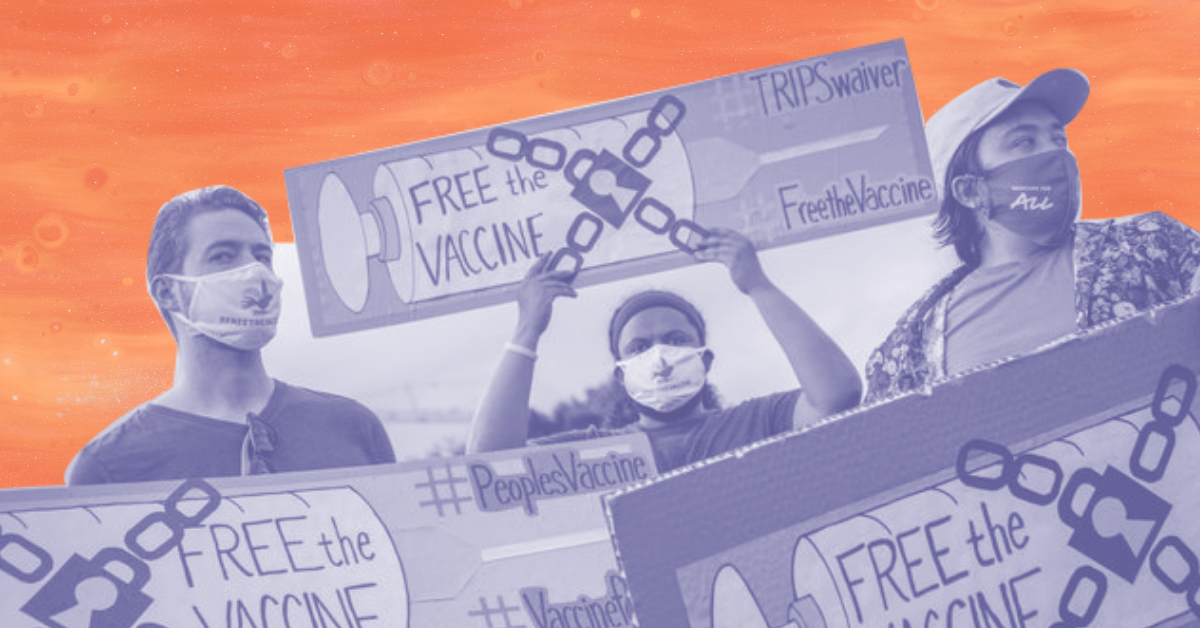

Access to life-saving medicines threatened

Signing RCEP at a time when the demand for a life-saving vaccine is at its peak, big pharmaceutical companies have the most to gain by raking in massive profits through strengthened intellectual property enforcement and protection mechanisms.

Signing RCEP at a time of a global pandemic is a perfect recipe for disaster. Notwithstanding the fact that RCEP adopts the baseline standards of the 1995 WTO Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement which granted patent monopolies to pharmaceutical products for a period of 20 years, it also introduces more aggressive patent enforcement provisions. For example, Article 11.64 of the Intellectual Property Chapter allows customs officers to suspend the shipment of medicines suspected of “patent and copyright infringement.”

This provision has a huge implication on the generic drug industry whose life-saving and affordable products can easily be mistaken as ‘infringing goods’ by customs officers who have no expertise in neither patents nor public health. Such instances can also be used by big pharmaceuticals to demand unreasonable compensation from, and further license to file lawsuits against legitimate suppliers of generic drugs in dispute settlement courts thereby jeopardizing the introduction of generic competition to domestic markets.

Further, Articles 11.41, 11.43, and 11.46[2] all seek to expedite the patent application processes ranging from adopting an electronic patenting system, faster examination process and other means to simplify and streamline procedures for the benefit of big pharmaceutical companies. Signing RCEP at a time when the demand for a life-saving vaccine is at its peak, big pharmaceutical companies have the most to gain by raking in massive profits through strengthened IP enforcement and protection mechanisms.

Land and resource grabs intensified

Under Article 10.3 of RCEP’s Investment Chapter, foreign investors shall be treated no less favorably than domestic enterprises. Once ratified, this implies that foreign investors can now easily purchase vast tracts of farmlands, mountain ranges, and riversides free from legal and constitutional impediments that may have stopped them before. Giving foreign investors the right to own land will only concentrate greater power and control at the hands of multinational corporations and will push out small farmers, small-scale food producers, and Indigenous Peoples in the process.

Many RCEP member states have restrictions on foreign ownership of land – and for good reason. These restrictions are meant to protect national interests and sovereignty from the agenda of big corporations who seek to own vast tracts of foreign agricultural land from the Global South only to convert them into industrial export crop plantations. Even before RCEP, agribusiness expansion and farmland acquisition has been the dominant trend as many oil palm plantations account for a large portion of land grabs in the last few years[3]. With the passage of RCEP, these last remaining protections will erode even further and push small farming communities deeper into landlessness, poverty, and hunger.

Likewise, extractive industries such as mining, quarrying, and logging stands to win from the further liberalization of investment provided by RCEP. Several of these extractive industry operations are located in areas of high biological diversity and with the presence of indigenous communities threatening their ancestral lands and pushing animal populations to the brink of extinction. With greater incentive to expand, mining, quarrying, and logging operations will further erode mountain and riverside topographies that have served as natural flood barriers for centuries.The environmental degradation and the erosion of natural landscapes caused by extractives will entail more catastrophic flooding, landslides and massive displacement during extreme weather events as what has been witnessed by the Philippines when supertyphoon Goni and other successive typhoons hit the region leaving massive devastation in its path.

Under Article 10.3 of RCEP’s Investment Chapter[4], foreign investors shall be treated no less favorably than domestic enterprises. Once ratified, this implies that foreign investors can now easily purchase vast tracts of farmlands, mountain ranges, and riversides free from legal and constitutional impediments that may have stopped them before. Giving foreign investors the right to own land will only concentrate greater power and control at the hands of multinational corporations and will push out small farmers, small-scale food producers, and Indigenous Peoples in the process. As such, RCEP will only aggravate land grabbing in the Asia Pacific region and undermine efforts towards food sovereignty, and sustainable consumption and production.

Seed privatization promoted

RCEP will add more burden to small farmers by criminalizing seed-saving practices. This is in tune to the agenda of big seed and agrochemical companies like Syngenta, Monsanto and Bayer who seek to ban such practices and supply their own genetically-modified seeds to farmers which in turn requires chemical intensive fertilizers exclusively sold by the same.

As if agricultural liberalization was not enough, RCEP will add more burden to small farmers by criminalizing seed-saving practices. This is in tune to the agenda of big seed and agrochemical companies like Syngenta, Monsanto and Bayer who seek to ban such practices and supply their own genetically-modified seeds to farmers which in turn requires chemical intensive fertilizers exclusively sold by the same.

According to Article 11.9 (Multilateral Agreements) of RCEP’s Intellectual Property Chapter[5], RCEP endorses the ratification of the 1991 Act of International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants or “UPOV 1991.” While the language may seem non-mandatory, a complementing provision in Article 11.48 mandates parties to enact laws and policies similar to that and consistent with the plant variety protection system provided by UPOV 1991.

By ratifying UPOV 1991 or passing similar legislation to the same effect, farmers will no longer be allowed to save protected varieties of seeds for the next planting season. This will force farmers to pay royalties to seed companies which represent 10-40% price markup compared to commercial seeds. Estimates from civil society groups suggest that adopting UPOV 1991 would result in a 200-600% increase in the price of local seeds in Thailand and up to 400% in the Philippines[6].

Local food production systems undermined

The Asia Pacific region accounted for 53% of food retail sales driven mainly by big groceries and supermarket chains[7]. Unfortunately, the rise of these food retail corporations also constitutes a lesser market share for local food producers whose products are unable to compete with highly subsidized imports. RCEP will further reinforce this trend.

According to Article 8.11 of RCEP’s Services Chapter[8], service suppliers which include big retail companies and supermarket chains, are allowed to operate in member countries without the need to establish local presence and without having to source food from local producers. In fact, any member state who imposes any such restrictions on these companies will be considered in violation of the treaty and subject to the rules of its dispute settlement mechanism[9]. This implies that service suppliers, who normally have their own global food supply chain can pick and choose cheaper food suppliers from abroad instead of procuring locally produced goods.

Conclusion

RCEP will officially enter into force two months after at least six ASEAN member states and three non-ASEAN member states ratifies the trade pact. With the current pace of deliberations, experts estimate that the trade deal could become effective late 2021 or early 2022. This is a critical period for people’s movements to push back against the relentless efforts to transform the region into an expansive investment playground designed to cater business interests and violate people’s rights and sovereignty in the process.

As one of the largest FTAs outside of the WTO, RCEP plays a special role in the ‘spaghetti bowl’ of FTAs in the region aiming to consolidate other existing trade relations in the ultimate objective of pushing neoliberal policies that otherwise could not be advanced at the multilateral arena of the WTO. With an open architecture framework, RCEP is designed to allow the future accession of other countries even after its ratification. Hong Kong has already declared its intent to join while RCEP member states continue to hope for India to reconsider.

RCEP will officially enter into force two months after at least six ASEAN member states and three non-ASEAN member states ratifies the trade pact. With the current pace of deliberations, experts estimate that the trade deal could become effective late 2021 or early 2022. This is a critical period for people’s movements to push back against the relentless efforts to transform the region into an expansive investment playground designed to cater business interests and violate people’s rights and sovereignty in the process.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed the vulnerability of developing countries which have become more food-insecure and industrially stunted by espousing the same old neoliberal policies promoted by the IMF-WB-WTO troika. And yet, governments decided to sign another mega-FTA that will further empower large corporations to restrict access to medicines, seize farmlands, mountains, and rivers, privatize seeds and destroy local food production systems.

The severity of the multiple crises these policies have created is felt mostly by poor farming communities and indigenous populations who are at the forefront of preserving people-powered sustainable consumption and production practices. But the social transformation necessary to achieve SCP and sustainable development in general, requires the adoption of an alternative trading system aligned with the key components of PP-SCP namely:

- People’s rights are protected and advanced in the whole production and consumption chain

- Self-sufficiency from the community to the national level is promoted through people’s sovereignty

- Social innovations and community actions towards SCP are encouraged and supported; and

- Accountability of corporations and governments is demanded and ensured

Like any other neoliberal trade pact, RCEP offers ‘more business-as-usual’ solutions to problems of its own making. If anything, RCEP is but a bane towards any prospect for sustainable consumption and production.#

[1]https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/rcep/news/joint-leaders-statement-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep

[2]https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/rcep-chapter-11.pdf

[3]https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5492-the-global-farmland-grab-in-2016-how-big-how-bad

[4]https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/rcep-chapter-10.pdf

[5]https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/rcep-chapter-11.pdf

[6]https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5741-how-rcep-affects-food-and-farmers#gid=1493795463

[7]https://retailasia.net/stores/in-focus/whats-driving-growth-in-asia-pacifics-retail-industry

[8]https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/rcep-chapter-8.pdf

[9]https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/rcep-chapter-19.pdf