The goal of the World Bank’s Maximizing Finance for Development is to establish the central role of the big private sector in development, and encourage private sector-friendly reforms.

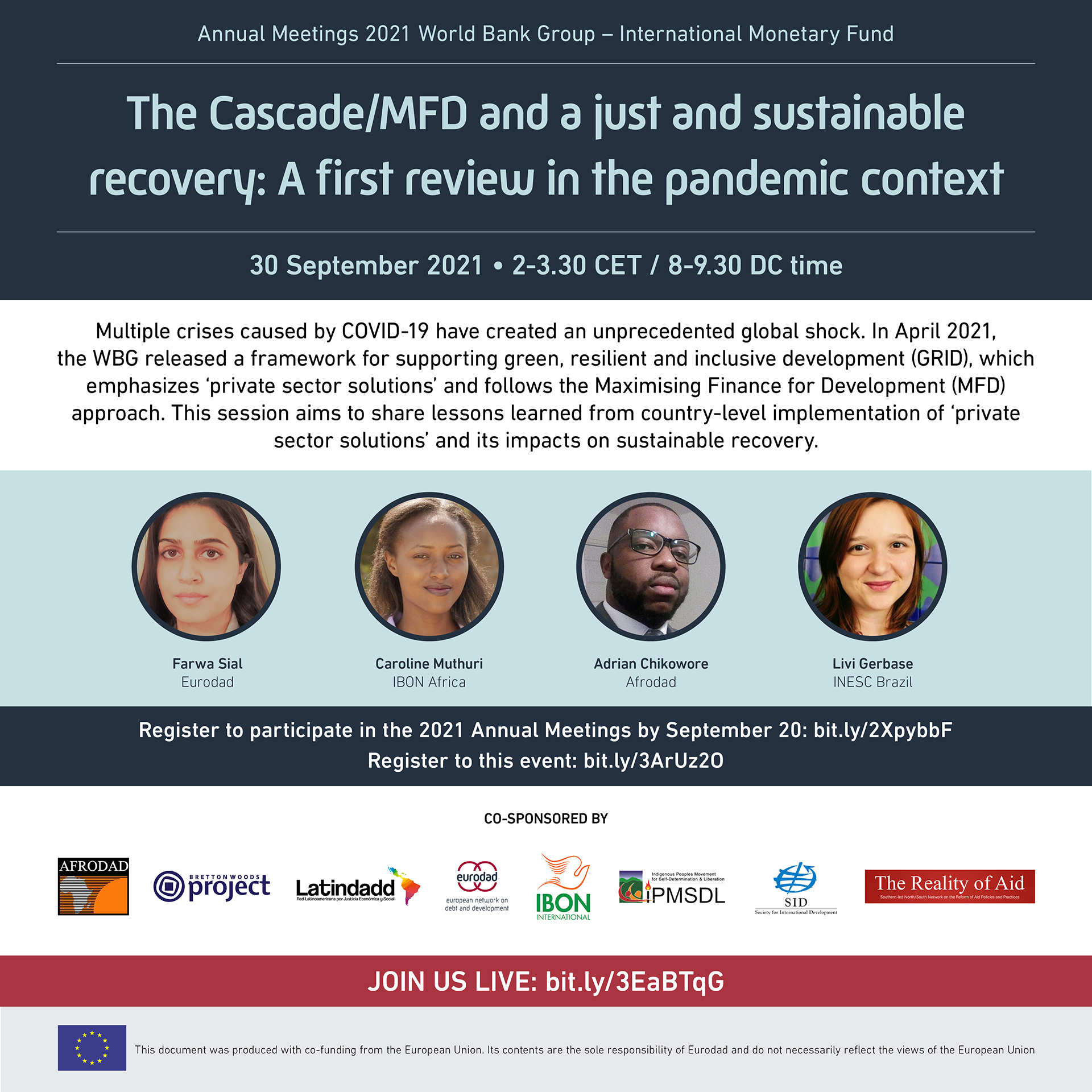

Caroline Muturi of IBON Africa delivered the following input on the World Bank’s Cascade Approach in Kenya at the Civil Society Policy Forum (CSPF) session, “The Cascade/MFD and a just and sustainable recovery: The first review in a pandemic context.” The CSPF session was held before the October 2021 Annual Meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group.

When the World Bank Group (WBG) first launched the Maximising Finance for Development (MFD), it identified nine pilot countries for its implementation, including Kenya. These so-called pilot initiatives predate the MFD and were only re-labeled as MFD initiatives. The goal of the MFD, of course, is to establish the central role of the big private sector in development, and encourage a host of private sector-friendly reforms such as public-private partnerships (PPPs), trade and investment deregulation, privatising or minimizing the role of state-owned enterprises, among others.

In the case of Kenya, the WBG cited private sector energy investments as MFD ‘success stories’, including projects that dated back to 2000. But a closer examination of these MFD projects expose how the interests of the big private sector do not align with a country’s broader social developmental objectives and sustainable development commitments, and even hinder their realisation.

The WBG has claimed to reduce investments in new coal power plants as part of its efforts to address climate change, but investigative research by civil society shows otherwise.

In Kenya, the WBG has financed dirty energy through its support of general infrastructure investment incentives, especially through PPP frameworks, which has enabled subsidies to flow to fossil fuels, including coal and upstream oil and gas.

It played a major role in the development of the Lamu Coal Plant, including in its power purchase agreement. The Lamu Coal Plant is a PPP project between the Kenyan government and Amu Power. It is opposed by local communities for its adverse impacts on their livelihood, health and culture. It also has already displaced farmers and Indigenous People. The WBG has also provided financing to Lamu coal plant through the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the WBG’s private sector arm. Commercial banks that have received funding from the IFC are known to have provided support to Amu Power and one of its major shareholders, Centum Investment.

The WBG also served as the transaction advisor for other PPP projects including the 980-megawatt Lamu Coal Plant, the Lamu Port Development Project (including Oil Refinery and Pipelines), and the 960-megawatt Kitui Coal Plant. It also provided technical assistance for the South Lokichar Oil Basin and Oil Pipeline project.

In June 2021, the WBG loaned USD 750 million to Kenya for “the country’s recovery”. One of its identified priorities is reforming the country’s energy sector toward economic and clean energy alternatives. However, the WBG fails to assure that the recovery package will not be used to finance or incentivise fossil fuel investments.

The policy reform vows to help strengthen Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) which revenue has dropped because of onerous power purchase agreements with independent power generators and has been the cause of high electricity costs in the country. Given the WBG’s insistence on the central role of the private sector in COVID-19 recovery plans, Kenyan civil society raises concerns that the reforms would push the privatisation of the energy sector.

The principle of democratic ownership is paramount in ensuring people’s sovereignty in defining the development pathway that they would like to take, and the appropriateness of projects to country contexts, priorities, and peoples’ development needs.

The WBG continues to champion the corporate capture of development in the guise of pandemic “recovery”. In this light, we share the following recommendations toward building people-centred development:

- Reinstate the importance of public finance and investment for achieving development goals. Whereas the private sector is driven by profitability, states are bound to deliver on the development needs of people and are better placed to address systemic issues such as inequality, poverty, and climate crisis. The principle of democratic ownership is paramount in ensuring people’s sovereignty in defining the development pathway that they would like to take, and the appropriateness of projects to country contexts, priorities, and peoples’ development needs.

- The World Bank is still far from truly aligning its operations according to the Paris Agreement. As shown in their operations in Kenya, the World Bank has failed to close policy-based assistance loopholes in its climate pledges. It should start by including development policy finance, technical assistance, and advisory services in all its climate pledges.

- Finally, financing for development should not limit the options to the policy prescriptions of privatisation, liberalisation, and deregulation. Instead of a recovery that merely revives pre-pandemic norms, we need to consider cancelling Southern countries’ debts, taxing multinational corporations and ultra-wealthy capital-holders, and fulfilling commitments in aid quality and quantity–all these require ambition for more systemic reforms. #