The TRIPS waiver can help make the production of life-saving products for developing nations affordable by temporarily eliminating some of the barriers to the access of knowledge in producing the vaccine and other medical products for controlling COVID-19. In the end, the waiver could protect billions of people.

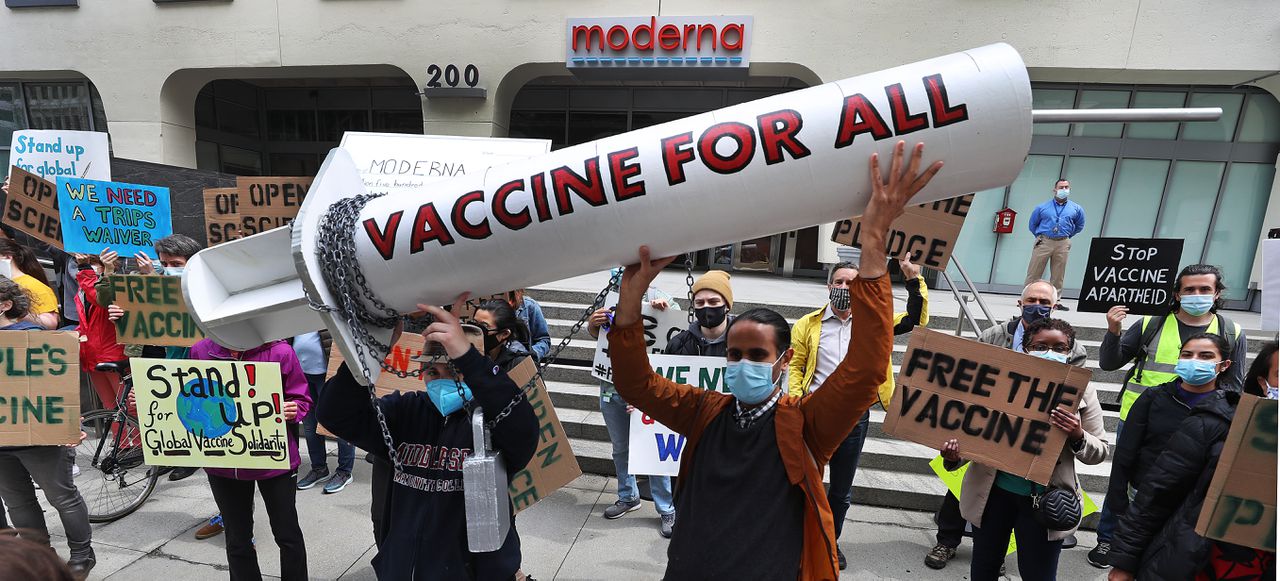

The World Trade Organization’s 12th Ministerial Conference (WTO MC 12), originally scheduled in Geneva on November 30 to December 3, has been postponed due to the surge of the new Omicron variant of COVID-19. Despite this postponement, negotiations on various trade issues would continue. For many campaigners and social movements around the world, the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement is still an urgent issue in the negotiations.

What is TRIPS? Why is its suspension a key element in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic? How does moving beyond the TRIPS regime help build sustainable development and people’s rights-enhancing economies for all?

What is TRIPS?

The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is a multilateral agreement in the WTO designed to protect patents and copyrights internationally.

Intellectual property is commonly defined as products of the mind. These include virtually anything produced from ideas, such as books, songs, paintings, films, and scientific advancements such as software, algorithms, medicines, vaccines, and surgical procedures. Patents and copyrights, on the other hand, are intellectual property protection regimes that grant licenses for the sole or exclusive right to make, use, or sell a creation or invention for a set period of time.

These protections supposedly provide incentives for the creation of ideas and technology that benefit the public. TRIPS takes these protections to the global level. The agreement is binding to all the 164 WTO member-countries, and standardises the practice of protecting inventions among WTO members through copyrights, trademarks, industrial design, and patents held by their nationals. Included in TRIPS is the 20-year minimum period of patent protection from the date of filing.

The TRIPS agreement is the direct result of strong lobbying of 12 United States (US) corporations, particularly big pharmaceutical company Pfizer, to include intellectual property in international trade policy. Pfizer executives in the 1980s were included in the US President Reagan’s Council on Competitiveness and in the Advisory Committee on Trade Negotiations (ACTN), the latter ensuring coherence between the objectives of US businesses and US official trade policy.[i] Aside from Pfizer, the CEOs of the corporations IBM and Du Pont were also in the ACTN.

The ACTN worked directly with the US Trade Representative to design the services, investment, and intellectual property agenda in US trade policy. In 1986, thirteen major US corporations, namely Bristol-Myers, DuPont, FMC Corporation, General Electric, General Motors, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Monsanto, Pfizer, Rockwell International and Warner Communications, formed the Intellectual Property Committee which lobbied for an intellectual property agreement in what were then the negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Through political maneuvers and intense lobbying of US counterpart companies to the EU and the Japan governments, the TRIPS was eventually signed at the culmination of the Uruguay round of the GATT in 1994.

While the research and development of the COVID-19 vaccines has been largely financed by public funding, big pharmaceutical companies are fiercely against sharing the vaccine know-how.

Expansion of TRIPS: For super-profit, against people’s right to health and development

Intellectual protection rules have since become strict and expansive, resulting in the prevention of people’s access to products that are essential to fulfilling human rights. In 1998, during an AIDS crisis, 41 drug companies sued the government of South Africa when it amended its 1997 Medicines Act to make cheaper medicines available to the public.[ii] With prohibitive prices due to intellectual property protection, anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) were accessible in industrialised countries but not in developing countries, including in South Africa. Although the prices have significantly gone down as a result of strong people’s campaigns to apply flexibilities for AIDS treatment, patent abuse by corporations still resulted to profiteering and sky-high prices of other life-saving medicines.

Another case in point is Sanofi’s Lantus, the top-selling insulin treatment for Type 1 diabetes. In the United States (US), Sanofi filed for more than 70 patents of the drug, protecting it from generic or biosimilar[iii] competition until 2028. Each year, from 2012 to 2016, its price increased by 18% in the US, making treatment inaccessible to those who cannot afford the drug.Tragic effects to diabetic patients can arise from the rationing of the treatment. The range of what can be brought under intellectual property regimes has also become so broad that even plant and animal varieties, as well as their biological processes and genetic information, can be patented. Patenting them means they can be ‘owned’ and ‘sold’ by an individual or a corporate entity.

For the past decades, people’s movements and civil society organisations have been clamouring for the cancellation of TRIPS agreement as it upholds monopoly intellectual property rights over the people’s rights and welfare. This clamour has intensified during the pandemic as the COVID-19 vaccines were also covered by the agreement. Major manufacturers, such as AstraZeneca/Oxford, BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson&Johnson, hold the exclusive rights to the production and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines. In October 2020, India and South Africa requested that the WTO TRIPS Council consider a temporary waiver to suspend intellectual property obligations on vaccines and other medical products needed to control the COVID-19 pandemic. India and South Africa’s proposal comes from their need to strengthen their own manufacturing capabilities to serve the urgent needs of their citizens for vaccines.[iv]Admittedly, the vaccine is not the sole solution to ending the pandemic. But the TRIPS waiver can help make the production of life-saving products for developing nations affordable by temporarily eliminating some of the barriers to the access of knowledge in producing the vaccine and other medical products for controlling COVID-19. In the end, the waiver could protect billions of people.

Since its submission, the temporary TRIPS waiver proposal has gained the support of 105 countries, including the US. However, developed countries such as the United Kingdom (UK), Norway, Switzerland, and the European Union (EU) – including Germany – are still blocking the proposal.While the research and development of the COVID-19 vaccines has been largely financed by public funding, big pharmaceutical companies are fiercely against sharing the vaccine know-how. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), representing some of the largest drug companies in the world, continues to lobby in a way that prevents the sharing of important vaccine knowledge amid a pandemic.

The last TRIPS Council meetings, in October 13 to 14 and November 5, 2021, discussed the intellectual property response of the WTO to the COVID-19 pandemic. In those meetings, the EU pushed for its proposal to use compulsory licensing as an alternative to the TRIPS waiver. Compulsory licensing is one of the flexibilities in the TRIPS agreement, particularly “when a government allows someone else to produce a patented product or process without the consent of the patent owner or plans to use the patent-protected invention itself.”[v] While this measure may help with matters involving patents, it does not resolve non-patent intellectual property barriers that prevent access to trade-secrets and protected knowledge, data, and other know-how on products that could control the pandemic.

Compulsory licensing is also applied on a per-product basis, making it incredibly difficult for developing country governments to coordinate the application for compulsory licensing of all the possible medicines and products for COVID-19, especially in a situation where the crisis is continuously evolving. In contrast, the TRIPS waiver calls for a general suspension of the application of the intellectual property protection of COVID-19 on copyrights, industrial designs, patents, and protection of undisclosed information on vaccines, medicines, diagnostics, and other products that can help contain the pandemic.

Reports from the November 18 TRIPS Council meeting suggests that there has been zero progress in either the TRIPS waiver or even the EU’s proposal. As the negotiations would continue despite the postponement of the 12th Ministerial conference, sponsors and supporters of the TRIPS waiver must guard against the watering down of the proposal, or bargaining for more market access in other negotiation areas in exchange for the waiver.

Gross vaccine inequity stops the world from ending the pandemic by allowing the virus to further circulate and produce stronger and deadlier mutations. Moreover, the vaccine inequity further widens the inequalities within and between nations, which COVID-19 already exacerbated. Ultimately, it violates the right to development of people in developing nations.

COVID-19 vaccine response and People-powered Sustainable Consumption and Production

The current COVID-19 vaccine response under the TRIPS regime further exposes the dominant, unsustainable system of consumption and production.

Societies create rules that govern social relationships around the production of knowledge and the use of scientific and technological progress. These rules can either enhance or undermine the prospects of sustainable and people-centered economies.

The human right to “share in scientific advancement and its benefits” is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and is further bolstered in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, a treaty to which 169 countries have voluntarily agreed to be bound.

The human right to science compels states to ensure: access for all to the benefits and application of science for a dignified life; opportunities for all to contribute to science and scientific research; participation of individuals and communities in decision-making; and an enabling environment for the conservation, development, and diffusion of science. It is often described as an enabler of other rights, as it helps the fulfillment of the right to health, food, water, as well as the right to development.

However, the human right to science can be severely impeded. Intellectual property regimes regulate who can use and economically benefit from ideas and scientific advancement, as well as who can consume and have access to these, affecting the pursuit of needs and a life of dignity. Debates on intellectual property are concerned with balancing it along with the economic, social, and cultural rights also enshrined in the UDHR, such as the rights to health, housing, food, and water.

In two separate reports, the former Special Rapporteur on Cultural Rights, Farida Shaheed, clarified that existing intellectual property protection regimes are human constructions, and can be changed if need be, on how to organise social relationships around production, consumption, and trade.[vi] Intellectual property cannot be used to defend patents and copyright laws that are stopping people from enjoying the benefits of science, and from public participation in the creation of scientific advancements. According to Shaheed, there is no human right to patent protection.

The current international intellectual property protection regime embodied in TRIPS is inimical to the goals of ending the pandemic and building sustainable and people’s rights-enhancing economies. Analysed through the lens of People-Powered Sustainable Consumption and Production, the COVID-19 global vaccine response bound by the TRIPS agreement demonstrates an unsustainable system of production and consumption which violates human rights.

|

Box 1. What is People-Powered Sustainable Consumption and Production? |

|

Sustainable consumption and production (SCP) plays a key role in realizing the overall sustainable development agenda. However, current dominant approaches to achieving SCP do not adequately address the systemic issues of poverty, underdevelopment, and rights repression especially in the poor countries. In 2018, IBON International developed the human rights-based framework, People-Powered Sustainable Consumption and Production (PP-SCP), to address the fundamental weaknesses of the current dominant approaches to SCP. The PP-SCP framework has four key elements: 1. Protection and advancement of people’s rights in the whole production and consumption chain Aside from filling in the big gaps of mainstream SCP approaches which do not address people’s rights, the PP-SCP framework can also be used to introduce comprehensive and coherent reforms that will address structural barriers to sustainability. |

The charity-based, public-private partnership model of the COVAX facility was not able to prevent a free-for-all purchase of the vaccines. Developed countries were allowed to act on self-interest and capture the supply.

People’s rights were not protected and advanced in the production, distribution and consumption of the vaccine. The refusal of developed countries and big pharmaceutical companies to waive some of the provisions of TRIPS has resulted in the unequal access to life-saving medical products during the COVID-19 pandemic. This violates several human rights such as the right to health, the right to science, as well as the right to development, especially of people living in developing countries.

According to Dr. Tlaleng Mofokeng, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Physical and Mental Health, “as of 23 September, 2021, 43.9 per cent of the world population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, but only 2.1 per cent of people in low-income countries received it. Ninety percent of Africans are still waiting for their first dose, compared with almost 50 per cent of fully vaccinated in high-income countries. Data suggest that most people in the poorest countries will need to wait another two years before they are vaccinated against COVID-19.”[vii]

While big pharmaceutical companies are keeping the vaccine know-how to themselves, developed countries are hogging the available vaccine supply. According to Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and United Nations Special Envoy for Global Education, “today’s shocking gap between the vaccine-rich countries, where 70 per cent had been vaccinated, and the vaccine-poor countries, with only 2 per cent vaccinated, showed in stark relief that millions of people had been clearly denied their basic rights. It had been shown that there were enough doses to vaccinate the whole world by May next year by mobilising the doses of vaccine available in the West.”[viii]

Because of over-ordering, the richest nations “will be sitting on a vaccine stockpile of unused doses that are surplus to their requirements.”[ix] Vaccine hogging is partly to blame for the failure of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility to fulfill its targeted 2 billion vaccine donations to developing countries.[x]

The lack of transparency in the COVID-19 vaccine contracts means a lack of accountability towards the people’s right to health. The secrecy surrounding agreements signed by governments and manufacturers prevent public monitoring of vaccine delivery dates and prices. Lack of information on delivery dates makes it difficult to hold manufacturing companies accountable for failure to fulfil delivery commitments. Meanwhile, the lack of information on prices, makes it hard to monitor the equity in pricing, and hinders negotiations for fair prices, especially among low- and middle-income countries.

Reports also reveal that some low- and middle-income countries have paid higher prices for the same vaccines than high-income countries.[xi] For example, the AstraZeneca vaccine is priced higher in Uganda (USD7) and South Africa (USD5.25), in comparison to the European Union (USD3.50).[xii] While shipping and handling costs may have been a cause of the price differences, little information exists on how these prices were calculated because of the lack of transparency in the contracts.

This gross vaccine inequity stops the world from ending the pandemic by allowing the virus to further circulate and produce stronger and deadlier mutations. Moreover, the vaccine inequity further widens the inequalities within and between nations, which COVID-19 already exacerbated. Ultimately, it violates the right to development of people in developing nations.

Because of the pandemic, an additional 119 to 124 million people had been pushed back into extreme poverty in 2020, and the number of people living with food insecurity has increased to 2.38 billion. With unequal access to vaccines, developing country governments may continue resorting to lockdowns which result in job losses and unemployment, especially for those in the service and informal sectors. In some cases, this may provide authoritarian governments an additional pretext to clamp down on civil and political rights, such as lockdowns to prevent protests.

Developing countries face a massive debt problem. As countries are mired deeper in debt, public funds are siphoned off to debt servicing, making social spending less for health, education, water, housing, and social security.

Everybody is harmed by profit-driven COVID-19 vaccine response. But vulnerable and marginalised peoples in developing countries, intentionally being deprived of equal vaccine access, suffer the brunt of the vaccine inequity. Already, vaccine inequity is already leading to a two-track economic recovery. According to UNDP, “analysis suggests that the economic recovery rate is predicted to be faster for countries with higher vaccination rates, with about USD 7.93 billion increase in global GDP for every million people vaccinated. For low-income countries where vaccination rates are almost zero, the path to recovery will be long and uncertain unless urgent corrective measures are taken.”[xiii]

The unequal access to vaccines aggravates the lack of self-sufficiency of less developed countries and poor communities.The situation makes them dependent on the aid for vaccines and for keeping their economies afloat. The COVAX facility,which includes vaccine donations to low- and middle-income countries in its mandate, is part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator proposal by Bill Gates. This proposal was made against calls for pooling knowledge, open science, and a ‘people’s vaccine’, in the end blocking equal access to the COVID-19 vaccine while keeping market control for big corporations.[xiv]

The charity-based, public-private partnership model was not able to prevent a free-for-all purchase of the vaccines. Developed countries were allowed to act on self-interest and capture the supply. Meanwhile, vaccine manufacturers are earning sky-high profits from the pandemic. For example, Pfizer “expects to earn USD36 billion only from vaccine sales by the end of 2021, compared to their USD41.9 billion in total revenue in 2020.”[xv]

Prospects for economic recovery, much less for a sustainable and people-centered economic recovery, are already overshadowed by the looming sovereign debt crisis. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 35 to 40 countries are in debt distress. But some research organizations consider this as a gross underestimation and identified 100 nations that will face budget deficits because of debt.[xvi] Developing countries face a massive debt problem, which according to the UNCTAD, would require debt servicing that would amount to between USD700 billion to USD1.1 trillion for low- and middle-income countries, and between USD2 to 2.3 trillion for high-income developing countries.[xvii]As countries are mired deeper in debt, public funds are siphoned off to debt servicing, making social spending less for health, education, water, housing, and social security.

The lack of equal access to vaccines and medical treatment has become a fertile ground for misinformation, as people search for alternative cures that are more accessible but potentially harmful. According to the World Health Organization, “misinformation about [COVID-19] and vaccines appears to have gotten worse and is keeping people from getting the shots.”[xviii]

Peoples demand for a TRIPS waiver and sustainable, people-centered recovery

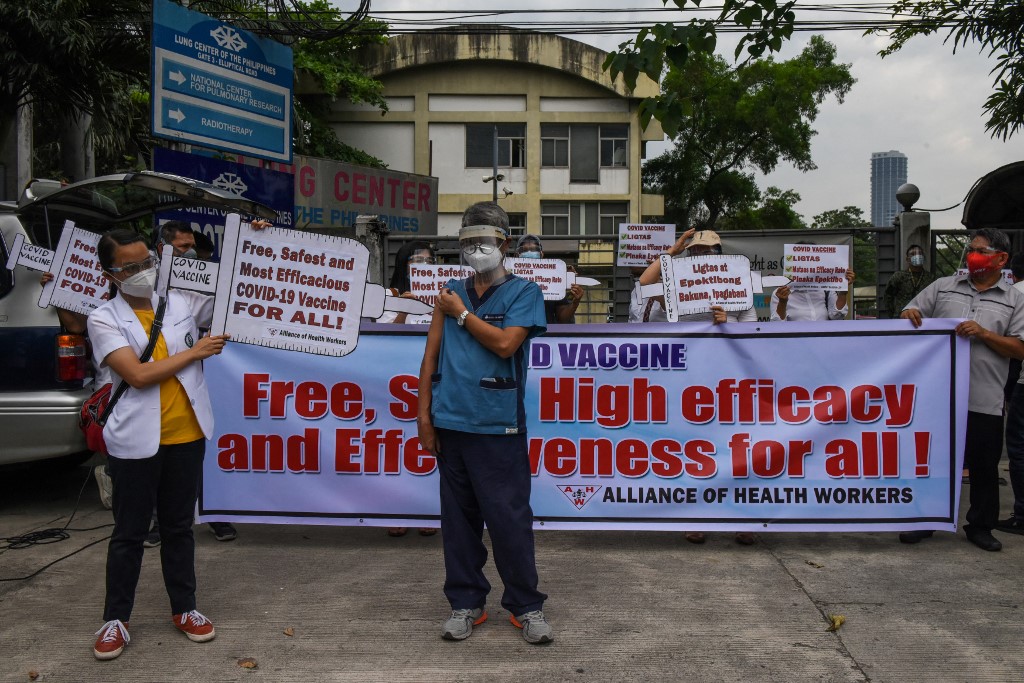

Since it is people who make intellectual property rules, they should also be able to change it. All over the world, civil society and grassroots communities are protesting to end the vaccine inequity and for the WTO TRIPS waiver. In Europe, activists organised the ‘Days of Shame’ to pressure the EU and European countries to support the TRIPS waiver. In the Philippines, local health coalitions demanded their government not to falter in their support for the TRIPS waiver.[xix] In South Africa, activists protested outside the embassies of the US, Netherlands, and Belgium to call on these governments to break the deadlock in the negotiations, and instead expedite the signing of the TRIPS waiver in the WTO talks.

Cuba’s recent move to share its Abdala COVID-19 vaccine and technology with developing countries shows that it is possible for countries to put solidarity into practice. In sharing knowledge and technology, they help each other meet their development needs and fulfill people’s rights, including the human right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications.

Aside from the TRIPS waiver and vaccine equity, communities have also launched actions towards securing the people’s right to food and right to health.

In the Philippines, information drives in urban poor areas, using handmade posters, show what can be done to keep people safe from the virus amid the cramped living conditions and inadequate access to water and sanitary facilities in these communities. Some communities which have been producing herbal-based medicines, use these now to help ease COVID-19 symptoms. Various volunteer-run community pantries and community kitchens have also sprouted across the country to promote access to food: a basic need that is also important in boosting the body’s immunity against COVID-19. These solidarity actions were however met with repression by the government. Some of the organisers were red-tagged by government officials and harassed by law enforcers.[xx]

In Indonesia, women farmers organised themselves to continue agricultural production for their families’ and their communities’ daily food needs amidst the government-imposed lockdowns. They enriched previously barren lands and actively shared their agricultural knowledge with each other. Organisers of these initiatives still emphasise that effective government action is necessary to address people’s needs during the pandemic.

In Kenya, civil society campaigned against sovereign loans, made in the name of responding to COVID-19, that were lost to corruption. Strong public uproar in the country, where online activists are using hashtags #StopLoaningKenya and #StopGivingKenyaLoans, mobilised Kenyans to sign petitions urging the IMF and the World Bank (WB) to stop lending to the Kenyan government.

While the demands for the temporary TRIPS waiver is gaining support, civil society and activists have long called for the abolition of the TRIPS agreement in the past WTO ministerial conferences. Stronger intellectual property rules in free trade and investment agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (CPTPPA) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have also been widely opposed. The way TRIPS is currently being used by developed countries and big pharmaceutical companies, for profiteering and prevent equal access to the vaccines, adds evidence for doing away with the agreement. Moreover, the current global intellectual property regime further exposes the power asymmetries between developing countries, on the hand, and developed countries, on the other, with dire consequences on people’s rights and lives.

Much can be learned from Cuba’s recent move to share not only its Abdala COVID-19 vaccine with developing countries, but also the technology.[xxi] This example of South-South cooperation shows that it is possible for countries to put solidarity into practice. In sharing knowledge and technology, they help each other meet their development needs and fulfill people’s rights, including the human right to benefit from scientific progress and its applications.

The principles of open sharing of knowledge and technology, or the principle of openness to modify, adapt, and develop scientific knowledge and technology, should be supported. Any intellectual property regime must be built around protecting human rights and promoting collective or public ownership and control of scientific processes and technological development. Likewise, knowledge, especially those belonging to indigenous communities, must be protected from private and corporate interests which seek to monopolise knowledge for profit. Such measures will enable developing countries and communities to go beyond access, towards owning knowledge and technology for their needs and as part of the public commons. In the end, such collective or public ownership could help build economies that are truly people-centered, environmentally sustainable, and human rights-enhancing.#

[i]https://www.grain.org/media/W1siZiIsIjIwMTEvMDcvMjUvMDZfMjhfMjRfNzUxX2RyYWhvc19mdGFfMjAwM19lbi5wZGYiXV0

[ii]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3078828/

[iii]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biosimilar

[iv]https://www.tralac.org/blog/article/15235-the-proposed-trips-waiver-to-respond-to-the-covid-19-pandemic.html

[v]https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/public_health_faq_e.htm

[vi]https://undocs.org/en/A/70/279; https://undocs.org/en/A/HRC/28/57

[vii] Speech during the Half-day panel discussion on deepening inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and their implications for the realization of human rights at the 48th Session of the Human Rights Commission, September 28, 2021.

[viii]https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx?NewsID=27559&LangID=E

[ix]https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/g20-vaccine-inequality-appeal-to-g20-by-gordon-brown-2021-10

[x]https://time.com/6096172/covax-vaccines-what-went-wrong/

[xi]https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/covid19-vaccine-arrangements

[xii]https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/covid19-vaccine-arrangements

[xiii]https://data.undp.org/vaccine-equity/impact-of-vaccine-inequity-on-economic-recovery/

[xiv]https://newrepublic.com/article/162000/bill-gates-impeded-global-access-covid-vaccines

[xv]https://www.businessinsider.fr/us/pfizer-2021-vaccine-revenue-close-to-2020-total-earnings-2021-11

[xvi]https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/sep/23/more-than-100-countries-face-spending-cuts-as-covid-worsens-debt-crisis-report-warns

[xvii] UNCTAD. 2020. From the Great Lockdown to the Great Meltdown: Developing Country Debt in the Time of Covid-19. https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=2710

[xviii]https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/24/who-says-covid-misinformation-is-a-major-factor-driving-pandemic-around-the-world.html

[xix]https://businessmirror.com.ph/2021/10/13/health-advocacy-group-asks-dti-to-back-TRIPS-waiver/

[xx]https://www.bulatlat.com/2021/04/20/cops-roam-around-community-pantries/

[xxi]https://peoplesdispatch.org/2021/10/21/cuba-vietnam-on-the-road-to-vaccine-self-reliance/