Water for the People Network

[[{“type”:”media”,”view_mode”:”media_large”,”fid”:”62″,”attributes”:{“alt”:””,”class”:”media-image”,”height”:”178″,”style”:”width: 310px; height: 178px; margin: 10px; float: right;”,”typeof”:”foaf:Image”,”width”:”310″}}]]

Last August, ADB released its 2012 Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific with a special chapter on Green Urbanization. In this report, ADB exalts Asia-Pacific’s sonic-paced urbanization as compared to other regions, such as Europe, North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. The report says that, in less than a century, 51% of the region has already been urbanized—with China, Bhutan, Laos, Indonesia and Vietnam leading the way.

This, the ADB claimed, is a sign of Asia’s economic prowess asserting itself in the global scene besides its apparent robustness in the midst of the struggling economies of the US and some European countries. ADB even alluded to urbanization being an indicator of human development, stating that, “It is generally accepted that city growth has made urbanites happier, healthier and smarter.”

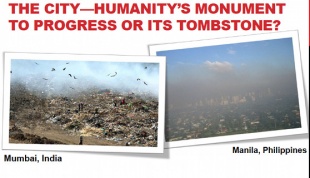

This is a curious statement, considering the gross inequality and increased incident rates of theft and murder that come with urbanization as illustrated by UN studies on the state of cities around the world and in Asia. It is also worth mentioning that 60% of the world's most polluted cities are in Asia and 67% of all Asian cities would not even pass the European Union’s air quality standard, which ADB admits in the same report.

ADB does not seek a stop or slowdown to urbanization. It even insists that Asia is not doing it fast enough, bemoaning that by 2050, the region would have only surpassed South Africa and trail far behind Europe and North America. It then argues that if Asia would follow a green path, then it can not only proceed but even accelerate its rate of urbanization. And according to ADB, a key measure of a city’s “greenness” is its ability to provide clean water, sanitation and proper waste disposal.

Now, before one can get into the specifics of how green cities will look and how they can be better in providing basic social services, such as clean water, one question worth asking is, “Is there a direct correlation between urbanization and poverty reduction?”

In its report, ADB states that, “urbanization helps promote innovation and technological progress, leading to higher productivity. These…help raise household incomes and firm profitability.” So, has urbanization raised household incomes and firm profitability? Let’s examine the facts.

Flipping through the corporate portfolios of two of the world’s largest water industry players for 2011, one will see that Suez Environnement and Veolia Water earned a combined 14 billion Euros. Now, flip through UN Habitat’s State of the World’s Cities. One will find there that the most unequal cities are also among Asia’s top financial centers with high GDPs, such as Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi.

This led UN Habitat to state that the benefits said to be brought by urbanization will be undermined by the increase in poverty that goes with it, particularly in cities determined by pre-existing power relations that enable or reinforce social inequity.

And with the inequality that cities breed, the disparity in income and wealth also affects access to clean water and sanitation. Consequently, rapid urbanization has an inverse effect on water coverage—as people worldwide who are living in absolute poverty can attest to. This is because communities or districts which are not considered “economically viable” by water concessionaires are left to tend to their own needs, relying most of the time on private water vendors which sell water at a price that can compete with oil.

Since those who have the capacity to pay are the ones with water pipeline connections, it would appear that water gravitates towards money. Similarly, power emanates from, or rather, is reinforced by gaining control over water. This becomes evident with big-ticket urban water projects won by companies of local elites in partnership with transnational corporations, which are primarily financed by conditional loans from the World Bank or ADB.

In Manila, Philippines, two among the country’s richest people, according to Forbes, have majority shareholdings in the two water companies that serve the city’s East and West zones. Meanwhile, water coverage in the country’s capital continues to be subpar to those stipulated in the concession agreement between the government and private concessionaires. This is now the subject of a Philippine congressional hearing of the House committee on good government and public accountability. ###

Originally posted on the Water for the People Network website.