In photo (©Bulatlat): A worker carries a sign saying, “JOBS NOT TERROR LAW” during a protest.

To commemorate Human Rights Day, we are releasing a series of articles highlighting the worsening rights situation in the Philippines under the Duterte regime. These will be compiled with a dozen similar articles and published as a book in January 2021. We are grateful to the contributions of people’s organisations and civil society.

By the Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research (EILER)

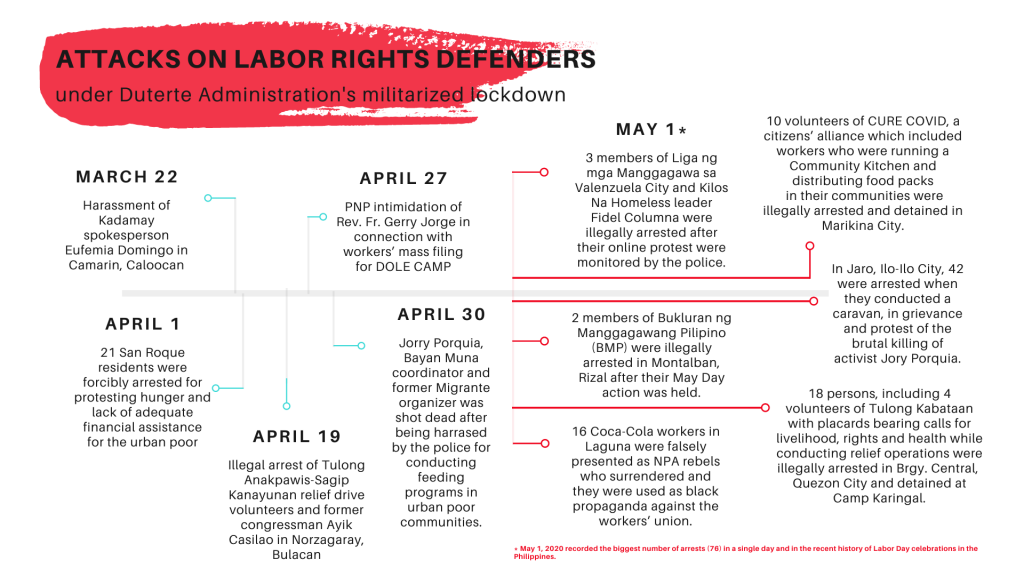

On December 10, International Human Rights Day, six labour organisers and one journalist were arrested in Metro Manila on trumped-up charges. Dubbed the “Human Rights Day 7,” activists are firm that so-called evidence of firearms and explosives were “planted” by state forces to conduct police operations, which they note is a longtime practice against activists and even in the course of the “drug war.”

Under the veil of curbing the pandemic, the Duterte administration unleashed its most brutal machinations in suppressing labor rights. The intensifying neoliberal attacks and state fascism made workers suffer record-high combined unemployment and underemployment, zero or close-to-zero wages, and the lack of social safety nets in this precarious situation – not just to salvage capital but even to take advantage of the crisis to maximize profits. To counter dissent against these machinations, the past few months saw extra-judicial killings, arrests, and demonization of the labor movement coupled with lay-off policies aimed at weakening labor unions.

Killings, arrests in lieu of assistance

The last couple of years were marked with exacerbated attacks against union strikes and protests. In 2018, striking workers of condiment company NutriAsia were violently dispersed, followed by arrests and mass lay-off. In 2019, picketing workers of surfactant company PEPMACO were violently dispersed and arrested. In the same year, several trade unions in Coca-Cola companies were harassed by tagging them as subversives. Worse, harassment of unionized labor even extended to killing labor organizers including Dennis Sequena and Reynaldo Malaborbor.

The year 2020 was a continuation of relentless attacks on trade unionists and labor rights defenders. The militarized lockdowns in the guise of community quarantine during the pandemic provided the government and capitalists alike a pretext to railroad anti-labor policies and intensify harassment of workers and criminalization of union activities.

At the onset of the pandemic, workers have emphasized the need for free and mass COVID-19 testing to curb the spread of the virus and mitigate serious social and economic impacts. However, this vital call fell on deaf ears and the government resorted to prolonged militarized lockdowns.

When the national government through the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) imposed the lockdown in March, millions of workers, in a blink of an eye, went jobless. By the end of April, unemployment rate peaked at 17.7% or 7.3 million Filipinos. This was more than three-fold than what was recorded the previous quarter at 2.4 million. Despite this grim situation, the first tranche of government assistance only came a month after the imposition of lockdown through the Bayanihan I, merely amounting to PhP 8,000 per family (approximately USD 166). Bayanihan I, short for Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, was the first pandemic response legislation of the Duterte administration. The law allotted around PhP 200 billion for assistance to 18 million families and other measures. The belated response to the pandemic on top of the neglect of the healthcare system halted economic activities in the major economic centers of the country and pushed millions of families further below the poverty line. These prompted expressions of dissent in the ranks of the working class that, as expected, irked the regime and big corporations as well as exposed their inutile handling of the pandemic.

May 1 recorded the biggest number of arrests in a single day and in the recent history of Labor Day celebration in the Philippines. A total of 76 workers and activists were arrested for participating in Labor Day protests launched in different parts of the country. The mass arrests included three (3) members of Liga ng Manggagawa in Valenzuela City together with Fidel Columbia, leader of Kilos Na Homeless on the basis of launching an online protest. Further, two (2) members of Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino (BMP) were arrested in Rizal province after their protest. Meanwhile, sixteen (16) workers of Coca-cola were presented by government forces as New People’s Army (NPA) surrenderees. The fake surrendering was aimed at demonizing unionized labour.

Development workers were also vilified. Ten members of the civic group CURE COVID were arrested for holding community kitchen in Marikina City. Another 18 relief volunteers were arrested while conducting a relief operation in Brgy. Central, Quezon City. In Jaro, Iloilo City, 42 individuals were arrested when they conducted a caravan in grievance of the brutal killing of activist Jory Porquia.

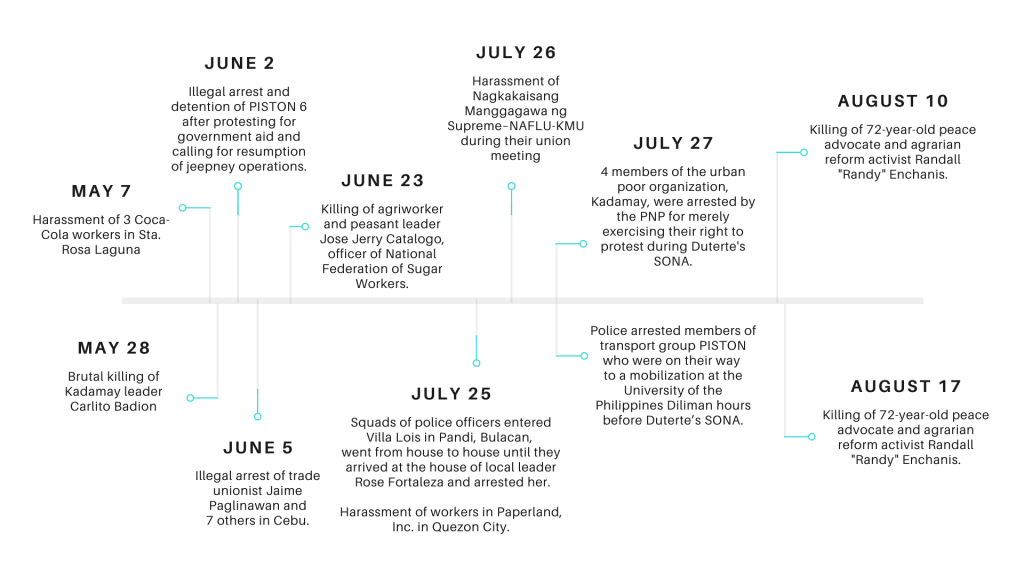

On June 2, six (6) jeepney drivers from the public utility vehicle driver-operator group, Pagkakaisa ng mga Samahan ng Tsuper at Operator Nationwide (PISTON) were arrested. They were protesting the stringent ban on jeepneys and other public transport during the pandemic, sans safety nets and assistance from the government. Four (4) of them were detained for six (6) days and the other two, including 72-year old driver Elmer Cordero, were detained for one week. A few days after, two (2) of them were confirmed to have contracted COVID-19 from jail.On June 5, government forces dispersed a peaceful protest against what was then the Anti-Terror Bill (now a law) in Cebu. Seven (7) individuals, including the veteran union leader Jaime Paglinawan of Kilusang Mayo Uno (Mayday Movement), were arrested. The basis of arrests was alleged violation to quarantine protocols.

On their way to State of the Nation Address (SONA) mobilization, five (5) members of PISTON and four (4) of urban poor group Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap (KADAMAY) were arrested. In total, 141 individuals from various groups were arrested while on their way to, during, or after protests (Umali, 2020).

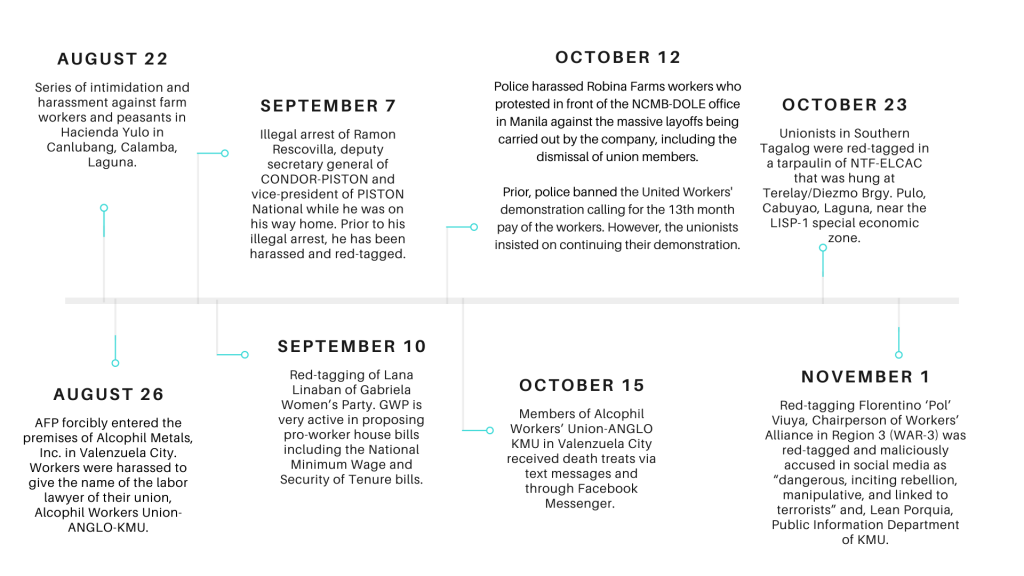

On August 26, members of the military barged into the Alcophil Metals Inc. and forced the workers to tell them the name of the lawyer of Alcophil Workers Union-Alliance of Nationalist and Genuine Labor Organizations-Kilusang Mayo Uno (ANGLO-KMU). Previously, in June, military personnel visited the company and declared that the union president is an “NPA recruiter” and the union is a “communist front.” The union members received death threats in October, again tagging their union as “communist front.”

On September 7, PISTON Vice-President Ramon Rescovilla was arrested on the false charge of homicide. The arrest came without prior subpoena from the prosecutor’s office, preliminary investigation, and the opportunity to submit counter-affidavit. Few hours prior, Bayan Camarines Sur Chairperson Nelsy Rodriguez was arrested.

In response to mass lay-offs in the meat supplier Robina Farms, on October 12, its workers protested at the National Concilation and Mediation Board of the Department of Labor and Employment office in Manila. The protest was met with harassment from the police force. Prior to the protest, the police also attempted to prevent workers from United Workers alliance to rally their call for the release of 13th month pay. Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III had previously hinted to Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez that companies considered “distressed” due to the impact of COVID-19 could defer the release of 13th month pay.The release of 13th month pay is considered mandatory under Presidential Decree No. 851, wherein employers from the private sector in the Philippines are required to pay their rank-and-file employees a 13th month pay equivalent to one-month of basic pay not later than December 24 every year.

On October 23, a tarpaulin tagging trade unionists as terrorists were hung at Terelay/Diezmo inCabuyao, Laguna, near the Light Industry and Science Park I (LISP I), a special economic zone or SEZ. On November 1, Florentino Viluya, chairperson of Worker’s Alliance in Region 3 (WAR-3) was red-tagged in Facebook as “dangerous, inciting rebellion, manipulative, and linked to terrorist”[sic].

On December 10, International Human Rights Day, six labour organisers and one journalist were arrested in Metro Manila on trumped-up charges. Dubbed the “Human Rights Day 7,” activists are firm that so-called evidence of firearms and explosives were “planted” by state forces to conduct police operations, which they note is a longtime practice against activists and even in the course of the “drug war.”

These were but a few cases of direct attack against the right of workers to organize and express dissent. The Duterte administration, amid the pandemic, has been wasting billions of pesos in funding bullets to liquidate union leaders, launch troll armies for an orchestrated vilification of organized dissent, intelligence operations to surveil workers, and other instruments to suppress the ever-growing labour movement.

The pandemic has exposed how the government further perpetuated plunder of resources, militarization, oppression of people’s collective rights and exploitation of the working class in pursuit of bigger profits for monopoly capitalists.

Lay-offs to weaken unions

As organized expressions of dissent intensify, corporations find this opportune time to suppress unionized labor. Under the veil of the pandemic, the supposed need to cut costs, lay-off workers was weaponized to drain the membership of workers’ unions.

In Robina Farms, 294 unionists were laid-off. The same company continuously hired new workers that are contract-based. Contract-based or contractual workers are not entitled to certain labor rights such as salary increase, social security benefits, and union rights.

In Jardin Schindler Elevator Corporation, around 130 workers were slashed from its manpower; eighty among them were union members.

Early retirement was the face of lay-offs in Supreme Steel. Around 50 workers who were also union members, retired prior to the compulsary retirement age of 65.

In Regan Industrial Sales, Inc., workers who were tagged as “high risk” to COVID-19 were offered with separation pays without even undergoing medical examination.

Banning jeepneys, railroading phaseout

The jeepney phaseout is another public-private partnership (PPP) carefully wrapped in neoliberal green agenda.

In the National Capital Region (NCR) alone, there are about 150,000 drivers and 50,000 operators. At the onset of the lockdown, jeepneys – one of the main forms and most affordable of public transportation in the Philippines – were banned from the road as part of the measures set by the government in curbing the pandemic. In an instant, millions of commuters, drivers and their families, were forced to greater economic insecurity.

Rubbing salt to the wound, other informal jobs that rely on the operation of jeepneys were heavily hit. The ban also led to closures of eateries, small stores,vehicle repair shops, and other businesses stationed in jeepney terminals. PISTON approximated that around 2.4 million individuals are directly and indirectly hit by the ban on public utility vehicles (PUVs). Most of them are living from hand to mouth.

Government assistance to PUV drivers only reached around 36,000 individuals. To make ends meet, many jeepney drivers resorted to begging in the streets as they were left with no other alternative. As many of them are life-long jeepney drivers, have no capital, and with the job market lean at present, begging became an inevitable recourse. To do otherwise will leave their families in hunger and unable to pay house rent and basic utilities. In an interview with PISTON president Mody Floranda, he said, “before, we wave our hands to the passengers to invite them to ride the jeeps; now, we do so to beg for help.”

There were reports, according to PISTON, that some of their members were evicted from their rented houses because they were unable to pay. While ordinances were passed against forced evictions during the pandemic, it did not prevent the same to happen in many cases. The evictions forced jeepney drivers and their families to live inside their jeepneys. This housing insecurity and homelessness expose mothers and their children to even more vulnerabilities. PISTON president Mody Floranda described this deliberate neglect as “depriving drivers not just of their livelihoods but even their dignity.”

It was only in June that the government allowed few routes to open. Yet, as was feared but expected, the government declared that it would proceed with the phaseout of jeepneys amid the pandemic. This policy was apparent as jeepneys, among other PUVs, were put in the last priority of those would be allowed to resume operations. The priority was given to ‘modern’ jeepneys, UV Express, and taxis.

Since 2017, the incumbent administration has been pushing for the phaseout of jeepneys. Under the pretext of reducing pollution, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) issued the Omnibus Guidelines on the Planning and Identification of Public Road Transportation Services and Franchise Issuances or Department Order 2017-011 (Omnibus Franchising Guidelines) in the same year. The issuance concretized the phaseout of jeepneys targeting primarily those 15 years or older. Old jeepneys will be replaced with ‘modern’ ones and will be manufactured by foreign corporations such as Isuzu, Foton, Fuso, among others. According to Floranda, the ‘modern’ jeepneys will cost PhP 2-3 million per unit, an amount unaffordable for many, if not most, of operators-drivers.

PISTON views this program as part and parcel of the Duterte administration’s continued adherence to and implementation of neoliberal policies on the transport sector.The proposed jeepney modernization was part of a larger Mega Manila Dream Plan that was first proposed in 2014 during the Aquino regime, with recommendations from the Japan International Cooperation Agency. In sum, the jeepney phaseout is another public-private partnership (PPP) carefully wrapped in neoliberal green agenda (EILER, 2017).

While the government was insistent with its phaseout policy, the move was met by serious contention by driver-operator organizations. As a result of the persistence of the transport workers, at present, there are about 35,000 jeepney units back on the road (San Juan, 2020). However, PISTON noted that it was still far from their demand of 100% ‘balik pasada’ or return to routes.

The pandemic has exposed how the government further perpetuated plunder of resources, militarization, oppression of people’s collective rights and exploitation of the working class in pursuit of bigger profits for monopoly capitalists through privatized and corporatized development of transportation infrastructure, public systems and social services.

The government’s complicity with foreign capital and their local counterparts put millions of toiling Filipinos in greater inequality and deeper impoverishment. The Duterte administration in subservience to big corporations is intolerant of organized and legitimate dissent as proven by its record of wanton human rights violations. The situation calls for even stronger unity among various sectors to counter the attacks against our fundamental freedoms and reclaim our rights.###

Sources

Interview of EILER with PISTON president ModyFloranda, September 4, 2020.

Independent tracking of human rights violations against workers by EILER.

EILER. (2017, December 11). Position Paper on PUV Modernization Program submitted to the Senate Committee on Public Services.

San Juan, A.D. (2020, November 17). More than 1,000 traditional jeepneys allowed back on roads. Manila Bulletin. Available: https://mb.com.ph/2020/11/17/more-than-1000-traditional-jeepneys-allowed-back-on-roads/

Umali, J. (2020, July 28). 141 arrested during nationwide #SONA2020 protests. Bulatlat. Available: https://www.bulatlat.com/2020/07/28/141-protesters-arrested-during-nationwide-sona-protests/