By Ivan Phell Enrile and Michael Gerochi

This article was originally published as an opinion piece on Rappler.

Climate finance should be reoriented towards the needs of developing countries. Mitigation presently receives most of the funding, but adaptation is a matter of survival for frontline communities.

From October 31 to November 12, parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change will be meeting in Glasgow, Scotland for the 26th Conference of Parties. Following the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warning that the world is on the way towards breaching the 1.5 degrees Celsius global warming limit in just two decades’ time, there is so much anticipation as to what this year’s climate talks will deliver, especially for communities in the frontlines of rising weather extremes.

What are the sticking points at the COP26 negotiations? What are the peoples’ priorities and demands for climate justice?

Climate fair shares

How the carbon budget will be allocated between developed and developing countries has been a long-standing debate in the climate negotiations. Which countries need to reduce or bring to zero their emissions? Which countries need to use the remaining carbon space for the development needs of their people?

The answer is that those who have built their wealth on fossil fuel extraction should take the lead in reducing emissions and support the most affected to adapt to climate change impacts and transition to sustainable development pathways.

But according to a civil society report, historical emitters are not going anywhere near the amount of emissions reductions they should undertake. In contrast, many Global South countries are meeting or even exceeding their fair shares.

Some developed countries have pledged specific targets to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, many of these targets are based on net-zero scenarios that allow for continued or even increased pollution based on the assumption that carbon capture technologies will be developed in the future to compensate for their emission. A successful COP26 should result in developed countries committing to a rapid and drastic phase out of fossil fuels, not net-zero targets by a distant date and that rely on unproven and risky technologies.

Developed countries should commit to a rapid and drastic phase out of fossil fuels, not net-zero targets by a distant date and that rely on unproven and risky technologies.

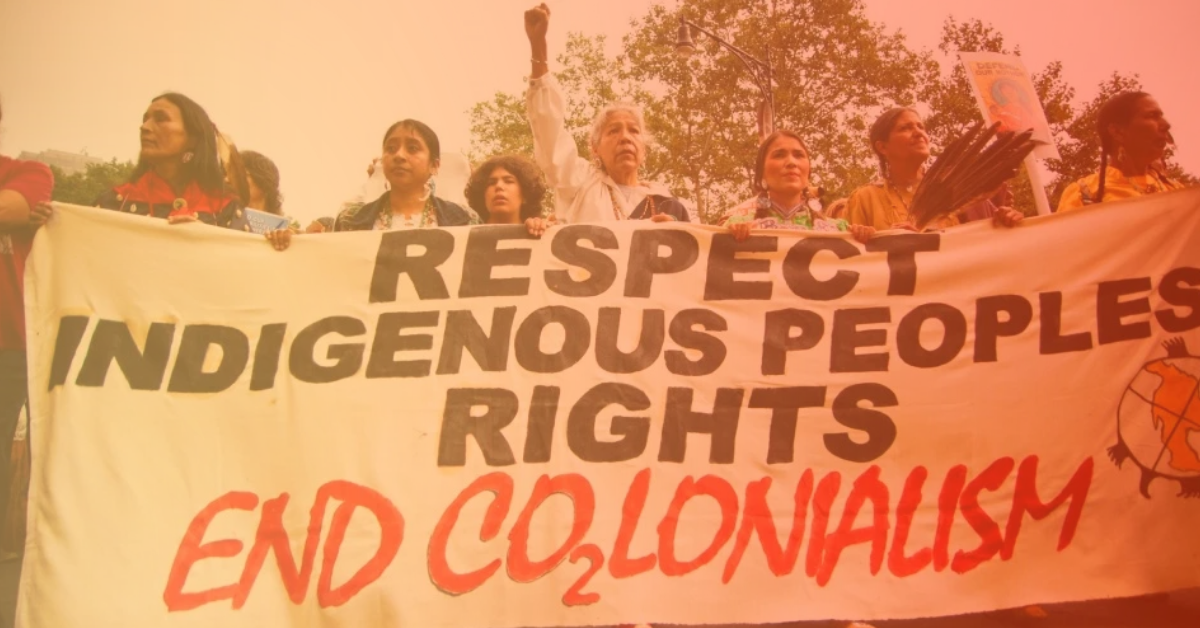

No deal on climate colonialism

Countries signed the Paris Agreement six years ago, but a few sticky issues remain unresolved, including the ongoing debate on the rules of implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement that deals with carbon markets and offsets.

Ambition-raising is core to the Paris Agreement. Carbon offsetting contradicts this spirit of the Paris Agreement because offsetting is a zero-sum game: it does not lead to global emission reductions since carbon reductions in one place are canceled out by continued pollution elsewhere. Offsets also create “hot air” or “excess credits” generated because a country has weak targets that it can easily overachieve. When these credits are sold to offset emissions somewhere else, they could increase overall emissions since they do not represent real emissions reductions.

Some parties are also pushing to use the credits generated before 2020 under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto Protocol. A study in 2019 estimated that there could be as much as four gigatons of emissions credits unused from the CDM regime because of lack of demand. The CDM has been riddled with problems since the start. Under the scheme, projects that would have happened anyway were rewarded with credits. Questionable accounting led to polluters receiving credits for dubious activities. If countries are allowed to use CDM hot air to achieve their already insufficient national climate commitments, the world will get even further off-track from reaching the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Indigenous peoples and human rights groups have warned that market-based mitigation approaches like offsetting are a possible gateway for a new era of climate colonialism. In Uganda, at least 22,500 people were driven away from their homes to give way to a carbon offset tree plantation by the UK-based firm New Forests Company.

Currently, there is increased pressure for COP26 to conclude negotiations on the Article 6 rulebook. However, a no deal is much better than a deal that can potentially undermine climate ambition, fail to deliver tangible benefits to the atmosphere, and violate the rights of indigenous peoples and vulnerable communities.

Indigenous peoples and human rights groups have warned that market-based mitigation approaches like offsetting are a possible gateway for a new era of climate colonialism.

Delivering just climate finance

Achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius is impossible without transferring huge finance from the Global North to the South.

At COP15 in Copenhagen, developed countries committed to mobilize $100 billion in climate finance for developing countries per year by 2020. More than a decade later, only a fraction of this promise is being fulfilled.

But developed countries are not only failing to meet their funding obligations. About 80% of climate finance comes in the form of loans or private finance instead of grants. For communities crippled by debt and burdened by the pandemic, increasing debt further hampers their resilience and deepens climate injustice.

Developed countries must pledge new public climate finance and agree on a concrete plan to deliver a minimum of $500 billion to developing countries between 2020 to 2024. COP26 should also acknowledge that economies need to mobilize trillions of dollars rather than billions when setting up the new public climate finance goal by 2025.

For climate finance to have credible impacts, it should be reoriented towards the needs of developing countries. Mitigation presently receives most of the funding, but adaptation is a matter of survival for frontline communities. A separate finance mechanism for loss and damages is also critical to delivering reparation and solidarity to communities for lives and livelihoods lost because of global warming.

When people and communities are at the helm of social governance and planning, they become officially and materially empowered to ensure economies meet human needs in ways that redress social and environmental injustices.

Putting people and the environment in the center of the climate agenda

A patchwork of policy reforms, however, will not suffice to get us out of the crisis. We need systemic change where people and the environment are at the front and center of development.

By democratizing ownership and control over productive resources, particularly in agriculture, transportation, energy, and finance, the wealth and benefits from each will be redistributed and reallocated for peoples’ needs, not monopolized by developed countries and large corporations for further expansion and profit. Democratizing ownership also entails the payment of reparations and the removal of unjust economic and trade policies that stunt developing countries’ growth and ability to adapt to climate change.

When people and communities are at the helm of social governance and planning, they become officially and materially empowered to ensure economies meet human needs in ways that redress social and environmental injustices, including economic, racial, colonial, and gender-based oppression.

Civil society will soon be holding mass actions around COP26 in Glasgow. Movements in the Global South that cannot go to COP26 because of lack of access to vaccines and impossible logistical requirements for traveling in a pandemic, on the other hand, will hold local mobilizations as a show of defiance and solidarity. All these efforts are made not because of the belief that COP26 will deliver the justice and change demanded by frontline communities, but to foreground peoples’ struggles and visions for a more resilient, just, and carbon-free world. #

Ivan Phell Enrile is the climate justice program manager of IBON International.

Michael Gerochi was an intern at IBON International and an incoming senior BA Development Studies student at Ateneo de Manila University.