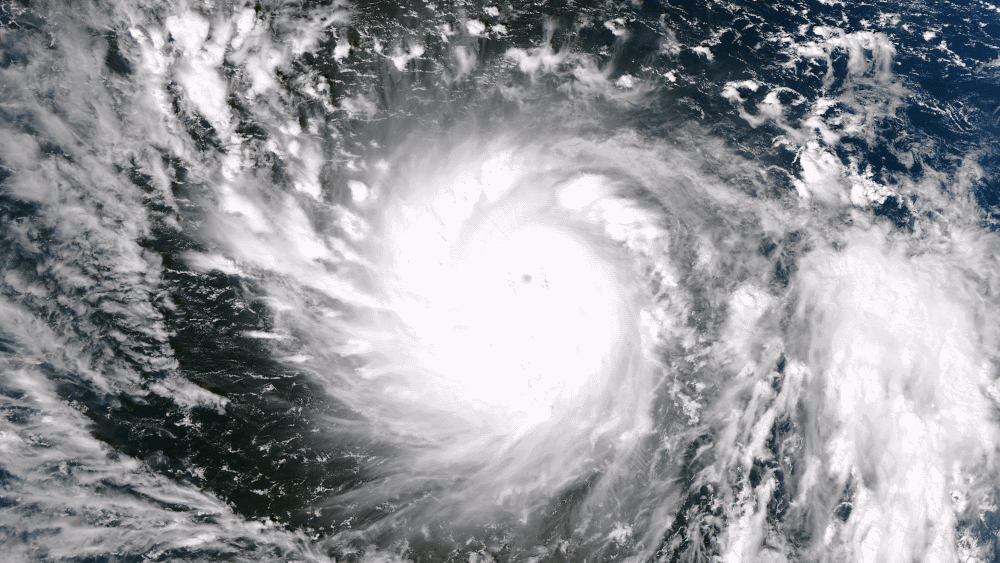

[[{“type”:”media”,”view_mode”:”media_original”,”fid”:”1890″,”attributes”:{“alt”:””,”class”:”media-image”,”height”:”435″,”style”:”width: 600px; height: 272px;”,”typeof”:”foaf:Image”,”width”:”961″}}]]Haiyan photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons with CC BY-SA 3.0 license . November marks four years since the supertyphoon.

IBON International Updates # 3

Climate Justice

November 15, Bonn – The annual climate summit enters its 2nd week, with the hopes of coming to an agreement on a rulebook that clarifies how the 2015 Paris Agreement will be realised as the global response to climate change. The 23rd Conference of Parties (COP 23) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is meeting in Germany with the government of Fiji presiding, with the objective of uniting different governments and other actors on how to keep global temperature increase well below 2 degrees Celsius, and if possible, below 1.5 degrees.

Sharp disagreements between developed and developing country governments have always been typical of the negotiations, and this is proven once more in this ‘Island COP.’ From the moment the talks opened, developing countries have insisted that the matter of ‘pre-2020 actions’ (covering the range of actions towards additional commitments to cut emissions as well as support for communities already feeling the brunt of climate change that governments would have to do before the Paris Agreement pledges take effect in 2020) be put on the agenda, which developed countries have been against of, arguing that they have almost already met their emissions reduction commitments and so the negotiations would now have to focus on rolling out the Paris Agreement.

Developing countries have expressed dissatisfaction on how very little progress is made on finance and adaptation issues. Under the UNFCCC principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’, developed countries have an obligation to provide resources to developing countries that have contribute the least to, but are feeling the worst impacts of, climate change. There is an existing goal of raising USD 100 billion annually by 2020, but funds raised and disbursed to date have been grossly inadequate.

Recognizing that adaptation is not enough to address the impacts of climate change, developing countries have also been pushing strongly that the COP 23 negotiations come out with decisions on losses and damages from extreme weather events (e.g. cyclones, hurricanes etc.) as well as slow onset impacts (e.g. sea level rise, droughts, etc.). There is an agreed ‘Warsaw International Mechanism’ (WIM) to tackle this matter, but agreement on who will foot the bill to get the work moving is far from coming. Many in civil society are critical of how loss and damage has been so low in the COP 23 agenda, and are also critical of how ‘solutions’ agreed on actually work more in favor of promoting private sector interest instead. One such example is the ‘InsuResilience’ initiative launched by Germany and Fiji yesterday, which seeks to facilitate (using public money) insurance coverage for people in developing countries.

The first ever Gender Action Plan (GAP) was adopted at COP 23. Many groups welcomed this as a milestone in efforts to move closer towards and financing gender-responsive and human rights-based climate policies. The GAP is seen as a critical tool to continue to demand climate justice – meaning, breaking free from fossil fuels, moving money away from the military-industrial complex and into social and environmental programs, promoting indigenous people’s rights, energy democracy and others.

[[{“type”:”media”,”view_mode”:”media_original”,”fid”:”1891″,”attributes”:{“alt”:””,”class”:”media-image”,”height”:”485″,”style”:”width: 600px; height: 323px;”,”typeof”:”foaf:Image”,”width”:”900″}}]]"Mind the GAP (Gender Action Plan)." Photo credit to WECF International.

Yesterday too, saw the adoption of the Indigenous Peoples Platform that would now allow for stronger indigenous voices not only in the official UNFCCC process, but also in designing and operationalizing programs and projects at community level.

While the overall picture is far from ideal, there have been some signals that allow for a bit of optimism, especially as there is a need for urgent and immediate measures to ease the burden of climate impacts. ###